Carcinisation

by James Waltz

edited by Kayla Sosa

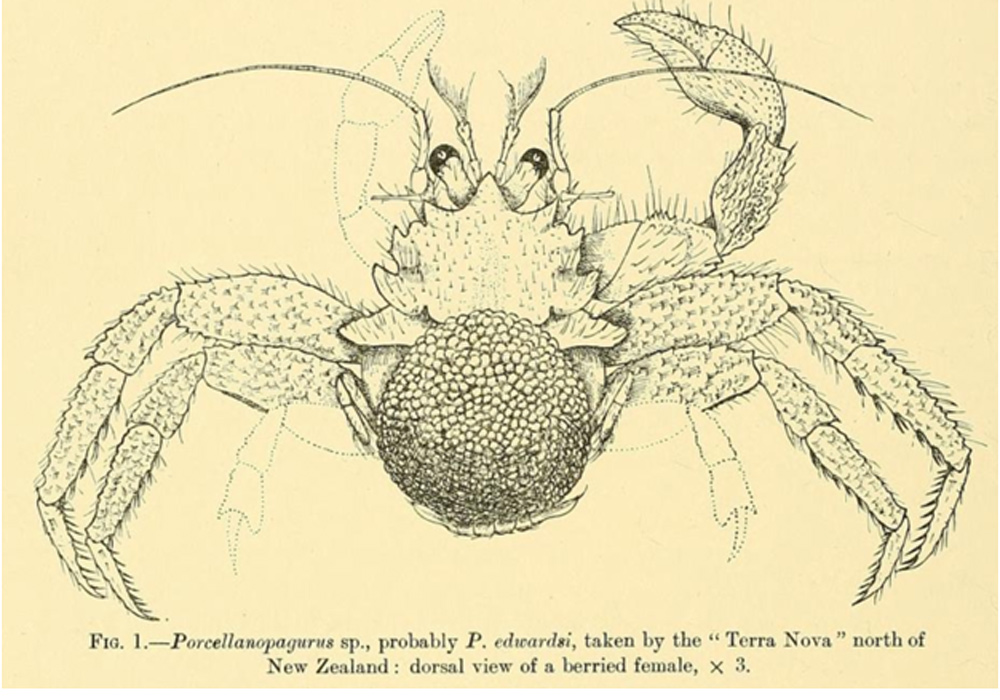

“Porcellanopagurus (Fig. 1) is one of the many attempts of Nature to evolve a crab…

“Porcellanopagurus (Fig. 1) is one of the many attempts of Nature to evolve a crab…

The tendency to carcinisation, emerging independently from time to time, has led in each case to different habits, but the obligation to the change must have lain always within, not without the organism.”

Of course, back then — Sibyl said — such a case was considered noteworthy. There was something fascinating about an animal turning into a crab. Those were the days when we had only started to notice this trend in a few scattered examples among species that already appeared somewhat crab-like to our eyes (plunged as they were in those strange, endoskeleton skulls that were in vogue at the time). We had no idea just how universal a phenomenon carcinisation was. Although it seems laughable, many were even skeptical of the reality of a process that, to us now, is as natural as water running downhill.

It’s easy to pass judgment on those that came before — Sibyl added as she picked some sediment from between her sternal plates — armed as we are with the collective knowledge we’ve accumulated since those dark ages. For an ape, the difference between a lobster and a crab is culinary, and the difference between a hermit crab and a crab is pedantry.

I, however, was starting to catch wise as to what exactly was going on. At the time, I was researching cases of convergent evolution, specifically these instances where various species evolved into more crab-like forms. Like most researchers whose knowledge is more academic than commodifiable, I was also teaching at the University. There I worked with Professor Q, who shared my interest in crustaceans, evolutionary biology, and Bach fugues.

As I pored over the published papers, I noticed that, over time, more and more species were foregoing their diverse anatomies in favor of something more crab-shaped. I won’t go so far as to say I had seen things through to the end, but I could feel the evolutionary momentum building, the way water flowing downhill carves a path for more water to follow, carving it deeper and deeper. It seemed clear to me this pull toward crabbiness was universal and accelerating.

Nobody took me seriously at that time, least of all Professor Q, who thought I was going mad. I even harbored my own doubts, although they were always intellectual in nature. The certainty, on the other hand, was something I could feel all over, like static electricity charging every hair on my body.

“Carcinisation is just a theory,” Professor Q reprimanded me one day. ”It is far more natural for the hierarchy to continue, where man stands proudly on top, closest to the almighty in whose image he was made. Below him sit the pincher-cat, the arachna-mouse, the Phthirus Pubis, and so on, like that… And women, somewhere in there, too,” he added self-consciously, as though he had suddenly remembered my gender. He cleared his throat awkwardly and returned to a quieter form of judgment as he gently scratched his pincher-cat behind its eye stalks.

While I lacked the evidence necessary to prove the universality of carcinisation, I decided to start taking some precautions. I walked always forward, never sideways. I also avoided backing up for fear of further shortening my (admittedly already somewhat stubby) thorax. Or, rather, torso.

I made a habit of stretching my fingers throughout the day and took up playing the piano to maintain their independence (though any listener would fairly question my success in that regard). I also fought the urge, tantalizing as it was, to bury myself in the sand on the beach and nibble at little bits of algae.

Despite my various prophylactic measures, I could tell I was losing the fight. My limbs were growing thicker, but my skin seemed thinner. My bones were like thick tubes that would emit a hollow thud when knocked.

My piano playing only worsened. Each day, my fingers’ ability to bend and splay weakened. Soon, it was impossible to play a single note at a time. I could only play cluster chords that even lovers of the spiciest experimental jazz would find jarring.

Worst of all, the urge to bury myself in the sand and slurp up algae grew more and more intense. Just the sound of waves made my whole body tremble with that forbidden desire and I could feel my eyes straining, bulging from their sockets. In the end, I swore to stay far from the beach so I wouldn’t succumb to that siren song.

Although my methods weren’t perfect, they did appear to slow down the process. Many of my colleagues had already completely transformed, even coming around to my theory (as their bodies changed faster than their minds). Some even went so far as to present my theory as their own at conferences to be greeted with a cacophony of enthusiastic claw-clacks.

Professor Q, however, remained unconvinced. If my care and diligence had slowed down the effects on me, his ire and indignation had granted him a similar result. While he had hardened, increased his limb count, and traded in his hands for pincers, he managed to maintain a somewhat elongated thorax compared to the others.

He also had his own ideas to describe the accelerating crabification of the world around him. “This talk of crabs is perfectly preposterous,” he hissed through flailing maxillipeds. “We are, as we have always been, lobsters at heart. The cultural-carcinisationists are leading to the decadence of our once glorious langoustine civilization.”

Seeing the professor fuming in unearned aggrievement made me question my own reluctance to accept my crab-shaped fate. I had fancied myself ahead of the curve when it came to recognizing this evolutionary imperative. Why, then, was I struggling so belligerently against it?

I found myself segmented both in body and in mind. As I scuttled back and forth lost in thought, I felt a deep nostalgia for my old body, soft and vulnerable though it may have been. At the same time, I recognized the futility of such wistfulness. There is no going back, no way, even, to halt the process that had started.

My doubts grew, and I began to believe that the best thing for me to do was to acquiesce to the metamorphosis at work within me. However, my routine of resistance had become habit by then, and though my mind was changing, my lifestyle wasn’t. Even the transformation of my body seemed to be slowing down more and more.

But that was when I met her. By that point, I rarely met anyone. Those who were once my family, friends, neighbors, and colleagues (with the exception of Professor Q) had long since completed their transformations and gone off to the beach or even deep into the sea. However, I did occasionally see someone scuttling through town, sometimes on their own or in large groups, but most often in pairs. I deduced that these crabs came from further inland, had transformed more slowly, and were only now passing through our town on their pilgrimage to the sea.

Klaria was one of those who made the journey alone. I had seen scores of the transformed, but none quite like her. I’m not sure what form she had before, but in her evolved state she most resembled a spider crab, although that does her no justice. Her long, slender chelipeds swayed gently as though she were conducting a slowly swelling string orchestra. The tangerine complexion of her carapace was variegated with shy, white freckles. I was instantly smitten.

She was taken aback when she noticed me, a common reaction from out-of-towners which I had become accustomed to, although, with her, it stung me. I must have appeared monstrous and chimeric in my halfway state. However, her demeanor softened after the initial start. She looked at me sweetly, opening and closing her pincers slowly. I returned the gesture.

I’ve never considered myself a cynic, but no one has taken me as a romantic either. I have generally had a fairly pragmatic approach to life which has served me well. I’ve gone on dates and even had a handful of long-term relationships where I loved and was loved. But with Klaria, it was different. I was swept away out of nowhere. My ventricle fluttered like a juvenile’s in her presence, and I wanted to always be by her side.

Eventually, we went to the beach together. It was the first time I had been there in ages. My wariness of that place had become second nature and filled me with anxiety, but I was determined. Klaria’s presence gave me strength on the journey. As we neared the sea, my tension began to wane.

The waves still echoed in my carapace, but I didn’t find them so deafening any longer. We sketched labyrinths in the sand and made ornaments of seashells and sponges. I felt at home with her and realized just how long it had been since I’d felt that way. I was ready to complete my metamorphosis.

I finally managed to abandon my old habits in my new life with Klaria, so I figured it was only a matter of time before my own carcinisation would be complete and we could move out to sea together. But my body wasn’t changing.

The previous transformations had happened without any effort on my part and, in fact, despite my efforts to the contrary. But, for whatever reason, my body seemed stuck in this taxonomic in-between. I embraced every crab-like behavior I could, I strained every fiber of my being trying to force my body to change, but all to no avail. Whatever evolutionary fire that burned before had since burned out. And I wasn’t the only one to notice. I could sense a growing lugubriousness in Klaria.

In both of our minds, our time spent at the shore, as much fun as we had there, was always a temporary stop on our way further out to sea. But in my half-state, I could never finish the journey. Klaria was always patient. She did her best to hide her disappointment and made the most of our time together, but I could sense she had been wanting to finish her own journey for a while.

One day, after she had slipped into the shallows to sleep, I traced a note in the sand for her.

My dearest Klaria,

These days with you have been some of the happiest I have ever known, happier than I thought I ever would know. But I cannot hold you back any longer. I will think of you every day, and I hope that someday I, too, will finally be fully crab. If and when that day comes, I will find you, but I do not expect you to wait any longer on me.

Love,

Sybil

Since then, I spend my days alone and inland. I have put my soul back into my anthro-arthropodological studies to keep despair at bay. I even sought out the company of Professor Q, but it seems that even he has moved on. I’m not sure if he ever became fully crab himself or if he still maintains his lobster body and mind wherever he is.

Some days, when the melancholy is more than I can stand, I go by the sea, collect shells, and think about where Klaria might be and what she might be doing. I can still feel some changes coming over my body, but they are so weak and so slow. At this rate, I know I will not live long enough to complete the transformation, but I still hold out hope that someday the evolutionary tide will rise again. If it does, I will be ready.

About James Waltz:

James Waltz is from Kansas City, Missouri, but currently lives in Barcelona, where he doodles and writes poetry, fiction, and music. Find him on Instagram @OrionBlueWaltz

For more from Mr. Waltz on Strangers & Karma, check out his collection of visual poetry and his prose, Moonrise, where he was featured in our Anthology.

Edited by Kayla Sosa, Managing Editor, Strangers & Karma

View her biography here. For inquiries or collaboration, please email.